Sculpture. A skill honed by our ancestors at the dawn of humanity, an art taken to a new level by the likes of Da Vinci and Michelangelo. As Henry Moore once said, “A sculptor is a person who is interested in the shape of things, a poet in words, a musician by sounds”. Yet it might seem that the world of modern sculpture was turned into a competition of scale, streamlined with record breaking sales and censorship scandal. In this controversial landscape, a true master emerges occasionally, and Jonathan Prince is exactly that.

His larger-than-life sculptures are uniquely influenced by his background in science, technology and medicine and his body of work is the expression of a 20-year investigation into these fields of study through the lens of his spiritual practice. Using the visual notion of duality to inform the viewer that non-duality is really what we should all strive for in our conscious lives, Prince brings poetry back into sculpture – and the practice of mindful observation of art back into our lives.

BRIGHT spoke to Jonathan Prince about his sources of inspiration, the ideal scenario of architect-sculptor collaboration and his stunning house-gallery-studio in rural Berkshire County (Massachusetts).

Interview by Anastasia Sukhanov

“The quest for perfection is a dream perpetrated by our egos, while precision is a goal that we humans can hope to achieve.” This is your Instagram intro, which is not something one would expect to hear from an artist. What is your trick for leaving space for chaos, chance, and inspiration on such a path?

One of the reasons that we do all our own fabrication at the studio is to allow for a dialogue between me and the other artist fabricators that work in the studio, and the materials that we are working with. We spend countless hours and trials to get the fabrication as precise as it can be. It’s very important for me to be able to work on a piece from start to finish, as I have a very hands-on approach – it connects me with the work. For example – stainless steel cannot be bent and shaped completely to our will and so the final works of art become a sort of collaboration between us. These areas that are out of our complete control are the ones that I find most intriguing and beautiful.

For you, the success ratio is “1% inspiration, 99% perspiration”. How do you get the 1% going? Is there an activity you turn to when you need top up your creative energies?

I am most inspired when I spend time thinking about the nature of life and how we can shape our consciousness by examining it. It’s part of the reason why I established the studio in the Berkshires of Massachusetts – the story of the barn, the nature surrounding me, the possibility of going cycling for miles every morning. It’s an exercise of connection and reflection, of energising and balancing. This is really what all my work is about – but of course through the lens of my experiences in science, tech, and medicine.

You’ve touched upon the origin of form and the beauty of its initial simplicity. What constitutes a perfect geometrical form for you, something that could always be a starting point in case of the architectural “blank page” syndrome.

I use geometry in my sculptural practice as a metaphor for truth and as a symbol for perfection. A physical object can never be perfect – but a mathematical formula like a Euclidean geometric axiom is… and so I use that as a foil to highlight the notion that real beauty is not found in the perfection of an object but rather in the breaks, tears, and scars. I believe this to be true as a metaphor for us as humans.

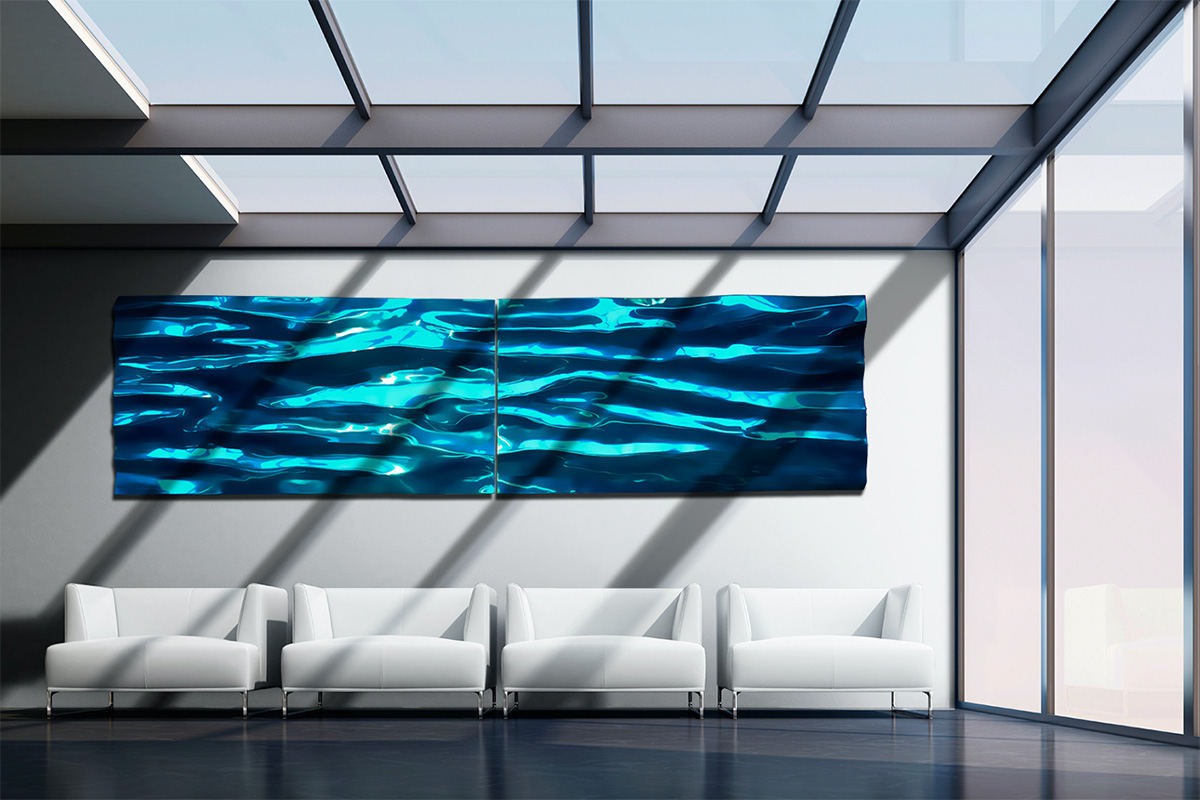

Your artwork stands out for a natural setting, and yet is in complete interaction with it through light and reflections. Is there a particular style of architecture and interior design that would best compliment it?

I really enjoy seeing my work in all types of settings both indoors and in nature. If we pay attention to our setting it influences our thinking and the way we feel – the same is true for a work of art and I don’t believe that one experience is better than another – just different. It is also once again a matter of dialogue and connection, my smaller pieces and works on paper are about the process and the selection as much as my large-scale sculpture. You relate to them in a similar fashion, they activate the space, especially when the light hits them. It creates a play of light and shadow prone to reflect on your own spirituality and life and it can hopefully encourage you to take a moment to reflect.

Do you think art should be an integral component of architectural planning rather than an afterthought put together by the interior design team?

This question is one that I think of often and I believe it depends on the artistic sensitivity of the architectural team. My ideal situation would involve the architect having a fully developed concept of their goals not just involving the aesthetics of design and function but also involving the feelings they are attempting to elicit from the visitors that pass through the space. This is where art can play a critical role and where I am the most interested in helping to determine how the art can help augment the experience.

If you could pick someone who you don’t personally know to ship your sculpture to, who would it be?

This is a difficult one. I see that different pieces that I have created through time could appeal to such a variety of people. Perhaps an idea for this one is to reflect on the reasons why I created my series Shatter – all the tears and breaks being exposed but also being connected in a way that is similar to Japanese philosophy of Kintsugi. So I think I would send this piece to a stranger that needs help in rebuilding their life and reconnecting the pieces together. Then I would love that person to send it to someone who is in a similar mindset and so on. Art can be a great healer, and this goes back to how I see everything as connected.

The house-gallery-studio you’ve built for yourself is stunning. What were your guiding principles when designing it?

I’ve always believed what architect Louis Sullivan said – that form follows function – and that has always influenced my design ideas around functional art such as furniture and architecture. My latest project in the house has been to select new furniture and my guiding principle has been to find pieces that reflect my own aesthetic or build my own pieces in the studio. I have created functional art for clients in the past and it is something that I enjoy a lot as I see the furniture becoming part of a whole, one element complementing or entering a dialogue with other materials you find in the house.

You’ve already experimented with AR, audio and haptic feedback as part of Berkshire House Digital. How do you see the future potential of digital integration for your creations?

I consider the best works of art as a sort of poetry and the idea of incorporating AR in the art as a way of expanding the core ideas into a longer form narrative which I call Augmented Storytelling. The object or image can be expanded from static to action states and the story can continue to evolve in a sustainable fashion allowing a work to maintain relevance over extended time periods.

The unavoidable 2021 question: how did you spend lockdown and what was your biggest takeaway from it? (Bonus: the photo of your house above features a living room swing, do you get to use it?)

As difficult as it has been during the pandemic to be alone for long periods of time it has also proven to be something that has given me the time to evaluate my life and consider the things that are most important. Having an open heart and appreciating the joy of leading a creative life are at the centre of that awareness. And yes… that swing is a part of my life – a reminder to find the fun and gratitude every day!