Article by Vivion O’Kelly

Some thoughts about something that’s supposed to mean something

This huge Marc Rothko painting, like many abstract works, must be seen in the original, given the difficulty of transmitting emotion alone on a small scale. (Source: Arte del siglo XX Published by Taschen)

Some people would prefer to have their fingernails extracted with pliers than see an exhibition of abstract art. At best, a random collection of shapes and colours that are supposed to mean something, and at worst, a century-old fraud perpetrated by a small group of pretentious connoisseurs on a gullible public. Both are true to some extent, in that some artists simply slap colours and shapes together and call it art, and some agents trade on the understandable desire most of us have to appear to be more cultured than we are. But my argument is that good abstract art can be appreciated by anybody who takes the time to acquaint themselves with the subject. I would also claim that beauty is generally not in the eye of the beholder, and that good art is, in the main, objective.

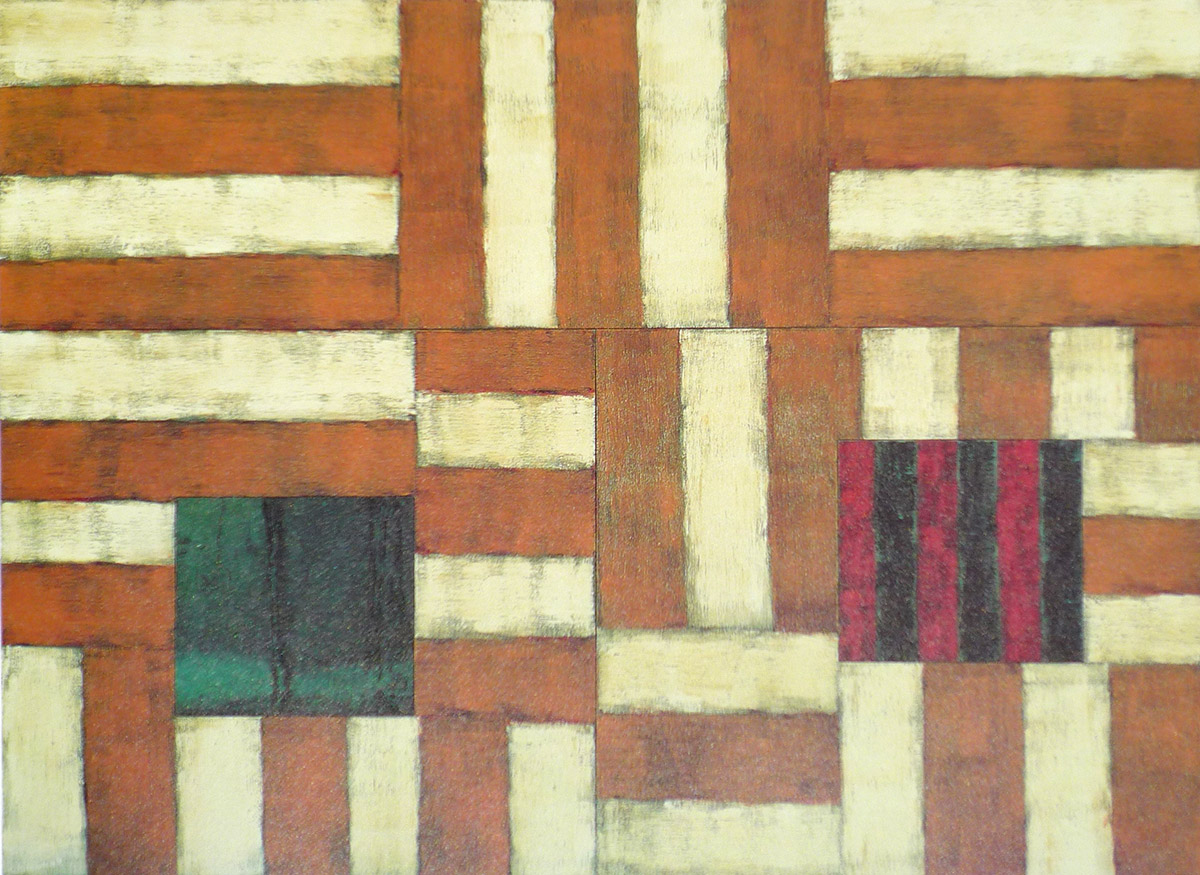

The Irish-born New Yorker Sean Scully is one of the most famous abstract painters of our day. In a long career, he has never deviated from what are basically thick, coloured lines. (Source: The 20th Century Artbook. Published by Phaidon)

And who decides what’s good and what’s bad? There are no absolutes, but that does not lend validity to the argument that art – especially abstract art – is entirely subjective, and therefore should not be defined. A simple definition might be elusive, but abstract art is, perhaps, best defined by differentiating it from representational art: in one, the marks on the canvas represent something and in the other they don’t. A bit like the difference between a song with words and a storyline, and a piece of music with neither.

Any child could paint that!

Well, yes, that is true of some abstract art. There are as many exceptionally gifted children out there who paint like gifted adults as there are exceptional child pianists and chess players. One of these art prodigies whose work can be seen on the internet is a Vietnamese child named Xeo Chu. Whenever a child’s painting passes a selection committee for inclusion in an important art show, nobody has been fooled, and when an abstract painting is hung upside down by mistake, it proves nothing other than that the artist should have signed it in the right place. The difference is that most of us have a more sophisticated appreciation of other art forms such as music and literature, and so are capable of knowing how good a child might play the piano by simply listening, while excellence in chess, to take another example, can be measured by just knowing who won. Compare the two paintings below –

The first is a rather sombre painting of a red circle and black squarish shape on a light background, and the second is a brighter and more exuberant painting of circles in reds and oranges on a blue background, somewhat child-like in execution. What’s the difference between the two? One difference is that the first was done by one of the leading American Abstract Impressionist painters, Adolph Gottlieb, and the second was done by my 12-year-old grandson, Nico. Is the second much better than the first? I don’t think so, and I believe Gottlieb would probably agree with me. Is my grandson a budding artistic genius? Of course not, no more than any 12-year-old who has been exposed to art from an early age and shown how to use oil paint on a large canvas.

Such a comparison has nothing to do with the value, both artistic and monetary, of the Gottlieb painting. There are millions of Nico paintings in the world, all done by children who had not yet fallen victim to society’s guidelines on artistic expression. Almost all are of unexceptional artistic value and worth nothing except to relevant Grandads and Nanas.

The apparently chaotic and random-gestural paintings of Jackson Pollock hide a controlled and systematic planning and execution. Again, no reproduction does it justice. (Source: Techniques of the World’s Great Painters. Published by Book Club Associates London.)

The formally trained Adolph Gottlieb, on the other hand, moved from an expressionist-realist style to a kind of surrealist abstraction, using motifs from the local environment in the Arizona desert to create, in his painting above, an almost purely emotional response to a landscape. The painting is one of his Imaginary Landscape series, in which the red disk loosely represents the sun and the black brushstrokes beneath represent the harsh desert floor. This makes the painting not totally abstract, of course, but the point of it is a more emotional than representational response to the landscape, just like any other abstract painting that does not represent anything but pure emotion. It took him a lifetime to paint this picture (or to be more precise, to be able to paint this picture), and having influenced generations of artists who came later, his work is worth a lot of money.

An early Kandinsky, showing him on his way towards pure abstraction. (Source: Arte del siglo XX Published by Taschen)

Where did it all begin?

It’s generally accepted that abstract art began as an early 20th century movement with artists like Malevich, Mondrian and Kandinsky. An article in the Observer newspaper, no less, repeats the story of Kandinsky returning home one night to his studio and seeing a magnificent painting that he could not make head nor tail of, in representational terms. It was his own painting upside down. They then claim that he denied this ever happened, to avoid trivialising the more serious origins of abstract art. It’s all patent nonsense. Long before he came on the scene, artists such as Cezanne and Monet had been abstracting certain aspects of painting, so the progression to complete abstraction was inevitable. To fully appreciate modern and contemporary art, one has to go back to artists like Turner and Goya.

It probably looks familiar, and that is because it is William Turner’s Snowstorm, upside down. (Source: 100 Masterpieces in colour. Published by Hamlyn)

What are we supposed to see?

This is the wrong question to ask: it’s more about what we are supposed to feel, by seeing. That does not mean that we are supposed to make of it what we will; that an abstract painting should be interpreted by each viewer according to his or her own imagination. It is certainly not a collection of random squiggles and colours that are open to interpretation by the viewer. A true abstract artist will generally put a great deal of effort into a painting in an attempt to express something specific (not representational), and if it is well done, the result will indeed do that.

Take the Rothko painting at the beginning of this article. Why would anybody ask what we are supposed to see in it, when its content is clear and simple? It is no more than a few rectangular shapes in a rectangular painting. Evidence of sophisticated technique is absent, deliberately hidden by the artist in favour of something more profound and spiritual that we can feel only if we are capable of looking at it without prejudice and with a certain knowledge of what the artist is attempting to achieve. But if Rothko really did express his feelings successfully in this painting, no explanation should be necessary.

With just a black square on a white background, this work by the Russian Kasimir Malevich, painted more than a century ago, may appear to be so minimalist as to be worthless. But he was the first artist to paint in this way, and that, more than any intrinsic artistic worth, makes the painting very valuable. (Source: Arte del siglo XX Published by Taschen.)

Abstract art is a bit like fine wine. To the uninitiated, a bottle of medium-priced Rioja will suffice, but we can all see that the more educated one’s taste becomes, the easier it will be to appreciate fine wine. It may be unfortunate that education is required to appreciate good art in general, but education, in this case, is no more than spending time on the Internet or visiting art galleries on a more regular basis. Abstract art is what it is, and nothing more should be made of it.